3 Types of Shoulder Replacement and How To Treat Them

Treatment GuidelinesWith the expansion of shoulder replacement options, patients can now achieve goals they once thought impossible. Let’s review the types of shoulder replacement available, prognostic impacts, and implications for rehabilitation.

How many of us have seen a senior patient with little to no functional upper extremity use due to severe rotator cuff pathology or pain? Before today’s shoulder replacement advancements, we could offer little to combat this functionally limiting diagnosis except activity modification and compensatory strategies. With the expansion of shoulder replacement options, patients previously ruled out as candidates for arthroplasty are now achieving goals they once thought impossible.

Advancements in shoulder replacement interventions have expanded greatly across the past 20 years. Individuals with end-stage arthritis, irreparable rotator cuff pathology and avascular necrosis can now reap significant benefits from these procedures.

In 2017, an estimated 823,361 patients were living in the US with some form of shoulder replacement with the prevalence continuing to increase.1 With the evolution of knowledge and surgical options, indications for shoulder arthroplasty continue to expand.

As rehab professionals, we must be well versed in these procedures and how they can benefit our patients. Let’s review the current types of shoulder replacement available, their prognostic impact, and implications for successful rehabilitation.

Anatomy Breakdown

First, a quick review of the anatomy of the glenohumeral joint will help us explore the strategies for shoulder replacement surgery.

As we all know, the glenohumeral joint is a ball and socket diarthrodial joint. It articulates between the humeral head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula. Movements at this joint include flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, external rotation, internal rotation, and 360-degree circumduction.

Generally classified as a mobility-dominated joint, movements occur in all three planes of movement. When treating patients with shoulder injuries, we must help them regain joint mobility while supporting their mobility with adequate stabilization.

As with any shoulder impairment, we cannot neglect the remaining shoulder articulations. Along with the glenohumeral joint, the sternoclavicular joint, acromioclavicular joint, and scapulothoracic articulation all comprehensively play into upper extremity movement.

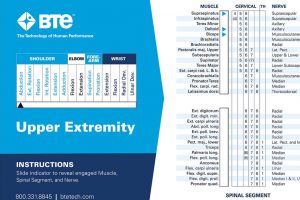

Looking for an easy way to reference these anatomical terms and functional relationships? Check out the Muscle Joint Action Guide by BTE – a quick guide for joint movements, muscle groups, and innervation of the upper and lower extremities.

Indications for Shoulder Arthroplasty

With an ever-growing bank of surgical techniques available, an increasing number of patients are reaping the benefits of shoulder replacement interventions.2 No longer is the procedure only advised for those with end-stage osteoarthritis, it is now open to many other diagnoses as well. Have a patient with any of the following? They may be a candidate for shoulder replacement.

- Inflammatory arthritis

- Rotator cuff arthropathy

- Massive or irreparable rotator cuff tears

- Proximal humeral fractures

- Osteoarthritis

- Avascular necrosis

Types of Shoulder Replacement and Implications for Rehabilitation

On to the good stuff. A deep understanding of each procedure helps with clinical decision-making and intuitive treatment during the rehabilitation process. With three main offerings, each arthroplasty procedure provides an opportunity for functional improvement.

Type 1: Anatomic Total Shoulder Replacement

The anatomic total shoulder replacement is the most popular and reliable form of shoulder arthroplasty today. It involves the replacement of both the glenoid and proximal humerus in an anatomic fashion. Surrounding rotator cuff musculature support the replaced joint powering upper extremity use.

As rehab practitioners, the most important factor to consider in this traditional form of replacement is subscapularis involvement. Almost always, the subscapularis will be cut and reattached to expose the joint.3 With tendon healing taking upwards of 12 weeks, it is imperative that we protect this repair during that initial timeframe.

Avoiding excessive shoulder external rotation stretching and internal rotation strengthening are key to ensuring proper healing. Although protocols may vary, sling wear is generally recommended for the first six weeks. This discourages active arm use and allows ample time for the repair to heal to the bone.

As far as long-term implications, the anatomic shoulder replacement procedure shows great outcomes in pain relief and upper extremity function. Patient compliance, quality of rehabilitation, and protection of the joint through activity modification are all imperative.

Lifelong lifting restrictions are limited to 40-45lbs to preserve implant integrity. Avoidance of repetitive lateral raises or heavy overhead presses will reduce rotator cuff strain and decrease risk of complications. Although formal physical therapy generally lasts fewer than six months, gradual improvement in pain and function will continue for 12-18 months following surgery.

Type 2: Reverse Total Shoulder Replacement

While traditional shoulder replacement provides excellent outcomes, the discovery of the reverse total shoulder replacement opened up new opportunities for treatment. Reverse shoulder replacement can benefit individuals with both glenohumeral joint deterioration as well as rotator cuff deficiency. This procedure provides pain relief and functional improvements for these individuals.4

As a unique approach, this strategy reverses the anatomic joint setup. Contrary to standard shoulder replacement, the prosthetic ball is attached to the scapula, and the socket is attached to the upper humerus. Without a functional rotator cuff, this opposing setup places the deltoid muscle in a more advantageous position to power movements of the arm.

When treating individuals following a reverse TSA, sling wear is recommended for two to six weeks post-op. Rehab will focus on gradual restoration of shoulder mobility and strength. However, you won’t need to be as concerned with subscapularis preservation because there is no tendon involvement. Instead, you should focus on protecting the joint from dislocation.

Patient education and treatment strategy should ensure avoidance of upper extremity weight bearing. Specific movements including combined extension / external rotation and adduction / internal rotation should be avoided to decrease dislocation risk. Lifelong lifting restrictions remain in place, between 25-30lbs to preserve implant integrity.

Type 3: Partial Shoulder Replacement

The third and least common of the shoulder replacement options is partial shoulder replacement or hemiarthroplasty. This strategy replaces only the humeral head and leaves the glenoid as is. Hemiarthroplasty is reserved for young individuals or those who are highly active and hoping to return to recreational or occupational weightlifting. Without fear of glenoid component loosening, post-op lifting restrictions are far less severe.

In performing a hemiarthroplasty, this procedure implies that the individual has well-preserved glenoid joint space and an intact rotator cuff interval. Various hemiarthroplasty strategies exist including the ream and run procedure. This approach replaces the humeral head and resurfaces the glenoid to seamlessly accept the shape of the new head.

When it comes to rehabilitation, noting subscapularis involvement is key. Similar to the traditional shoulder replacement, the subscapularis will almost always be detached and reattached. Be sure to consider this when curating your patient’s plan of care and making appropriate progressions.

Regardless of the surgical strategy, our main focus remains patient-centered care. We should strive to preserve the integrity of the joint while promoting pain relief and functional independence. Unfortunately, inconsistent protocols remain a large problem following TSAs and RTSAs. 5 To optimize patient results, maintain communication with referring physicians and examine individual protocols carefully. Understand that each patient will respond uniquely. The severity of the pre-existing condition, bone and tendon quality, and co-morbidities all impact prognosis and treatment strategy.

Final Thoughts

We’ve reviewed the anatomy, explored the types of arthroplasty available, and discussed our rehab implications. The final piece is education and implementation. A successful outcome for any shoulder replacement relies on a commitment to top-quality care, adherence to post-operative protocol, and an involved, compliant, and well-educated patient. Set clear expectations, educate your patient on both the what and the why of rehabilitation strategies and help them (quite literally) reach for the stars.

Morgan Hopkins, DPT, CMTPT

Morgan Hopkins, DPT, CMTPT is a physical therapist and freelance healthcare writer. She spent over 8 years treating patients in outpatient orthopedics before transitioning to medical writing. Her clinical specialties include intramuscular dry needling, dance medicine, and sports medicine. Morgan is extremely passionate about holistic wellness, preventative care and functional fitness and uses writing to educate and inspire others. To get in touch with Morgan, visit her LinkedIn or Upwork pages.

References

- Farley, K. X., Wilson, J. M., Kumar, A., Gottschalk, M. B., Daly, C., Sanchez-Sotelo, J., & Wagner, E. R. (2021). Prevalence of Shoulder Arthroplasty in the United States and the Increasing Burden of Revision Shoulder Arthroplasty. JB & JS open access, 6(3), e20.00156. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00156

- Mattei, L., Mortera, S., Arrigoni, C., & Castoldi, F. (2015). Anatomic shoulder arthroplasty: an update on indications, technique, results and complication rates. Joints, 3(2), 72–77. https://doi.org/10.11138/jts/2015.3.2.072

- Arslanian, L. E. (2005). Rehabilitation following total shoulder arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2005.2000

- Walker, M., Brooks, J., Willis, M., & Frankle, M. (2011). How reverse shoulder arthroplasty works. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 469(9), 2440–2451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-1892-0

- Bullock, G. S., Garrigues, G. E., Ledbetter, L., & Kennedy, J. (2019). A systematic review of proposed rehabilitation guidelines following anatomic and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 49(5), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2019.8616